Date with Death

by Clifford L. Graves, M.D.

September 1965A tense group of people was gathered on the freeway near the German town of Friedburg on July 19, 1962.

Herr Heinemann had painstakingly measured off the official kilometer. Half a dozen timekeepers of the International Timing Association were fiddling with their electrical equipment. Captain Dalicampt of the French occupation forces deployed his men at strategic points along the cleared Autobahn. Chief Schefold of the federal highway department dispatched a sweeper crew. Adolf Zimber lovingly wiped a bit of invisible dirt off the windshield of his massive Mercedes. Reporters were asking questions, scribbling notes. A photographer was angling for a shot. José Meiffret was about to start his Date with Death.

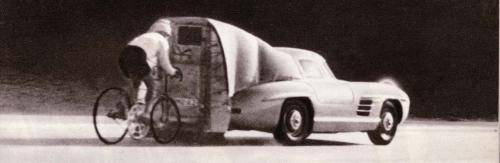

Of all the tense people, Meiffret was the least so. A diminutive Frenchman with wistful eyes and a troubled expression, he was resting beside a strange-looking bicycle. A monstrous chain wheel with 130 teeth connected with a sprocket with 15. The rake on the fork was reversed. Rims were of wood to prevent overheating. The gooseneck was supported with a flying buttress. The well-worn tires were tubulars. The frame was reinforced at all the critical points. Weighting forty-five pounds, this machine was obviously constructed to withstand incredible punishment.

On this day, at this place, on this bicycle, José Meiffret was aiming to reach the fantastic speed of 124 miles an hour. Everything was now in readiness. Meiffret adjusted his helmet, mounted the bike, and tighten the toe straps. Getting under way with a gear of 225 inches was something else again. A motorcycle came alongside and started pushing him. At 20 miles an hour, Meiffret was struggling to gain control. His legs were barely moving. At 40 miles, he was beginning to hit his stride. At 50 miles, the Mercedes with its curious rear end was just behind. With a wave of his hand, Meiffret dismissed his motorcycle and connected neatly with the windscreen of the Mercedes. His timing was perfect. He had overcome his first great hazard.

Swiftly, the bizarre combination of man and machine gathered speed. Meiffret's job on penalty of death was to stay glued to his windscreen. The screen had a roller, but if he should touch it at 100 miles an hour, he would be clipped. On the other hand, if he should fall behind as little as 18 inches, the turbulence would make mincemeat of him. If the car should jerk or lurch or hit a bump, he would be in immediate mortal danger. An engineer had warned him that at these speeds, the centrifugal force might cause his flimsy wheels to collapse. Undismayed b the prospect, Meiffret bent down to his task.

He was now moving at 80 miles. News of the heroic attempt had spread, and the road ahead was lined with spectators. Everybody was expecting something dreadful to happen. Herr Thiergarten in the car showed Meiffret how fast he was going by prearranged signals. Meiffret in turn could speak to the driver through a microphone. "Allez, allez," he shouted, knowing that he had only nine miles to accelerate and decelerate. The speedometer showed 90. What if he should hit a pebble, an oil slick, a gust of wind? Ahead was bridge and clump of woods. Crosscurrents were inevitable.

- In his pocket, Meiffret carried a note:

- "In case of fatal accident, I beg of the spectators not to feel sorry for me. I am a poor man, an orphan since the age of eleven, and I have suffered much. Death holds no terror for me. This record attempt is my way of expressing myself. If the doctors can do no more for me, please bury me by the side of the road where I have fallen."

Who was this man Meiffret who could ride a bicycle at such passionate speeds and still look at himself dispassionately?

He was born in 1913 in the village of Boulouris o the French Riviera. Orphaned at an early age, he had to got work to support himself and an aging grandmother. One day, as he was hurrying home from work on his ancient bicycle, he was run down by a motorist. José was badly shaken, and his bicycle was ground to bits. Distraught, the motorist offered to buy José a new bicycle. It was a beauty. Before long, his bike was his life. When he wasn't riding, he was reading. Under the skinny frame and deep-set eyes burned a fierce ambition. Someday he was going to beat the world.

His first race was a fiasco. Totally unprepared, he entered a 120-miler through the mountains and was promptly dropped. His competitors made fun of him, and a doctor told him that he had a weak heart and should never race. That night José cried himself to sleep.

The man who changed José's career was Henry Desgrange, the

founder of the Tour de France. Desgrange had a villa on the Riviera,

and José wrangled an introduction. Desgrange sensed the compelling

drive in the delicate body, and he made an accurate assessment,

"Try

motor-paced racing, my boy. You might surprise yourself."

José did just that. With fear and trepidation he entered a motor-paced race between Nice and Cannes. Without any indoctrination whatever he was immediately at home. Riding smoothly and elegantly, in perfect unison with his pacer and in complete control of himself, he was out front all the way and finished a full seven minutes ahead. The people went wild.

Encouraged by this success, he arranged to go over the same course behind a more powerful motor. This ride was an epic. Intoxicated by his speed, he barely missed a car in Nice, grazed a dog in Cannes, scraped a sidewalk in Antibes, had a flat five miles front the finish, and yet hung up a new record of 1.02 for the 40 miles. He had found his destiny.

How could a rider like José make a splash before he had caused a ripple? Racing behind motorist is quite different from racing in a group. Behind motors, the speed is higher, the pedaling faster, the concentration greater. It is like a continuous sprint. A motor-paced rider must have suppleness rather than strength. And he must have flair.

But a motor-paced rider is not made overnight. Just as José was beginning to hit his stride, the war broke out. When he returned to Paris after five dreary years of captivity, he was as far from his goal as ever. Motor-paced racing has a long and honorable history, but only a few men have ever excelled in it. In America, the sport died after "Mile-a-Minute" Murphy did his amazing ride behind a Long Island Railroad train in 1899. In Europe, the sport survived. On the road, the hour record was set in the thirties by the Frenchman Paillard with 49.362 miles. Meiffret raised this in 1949 to 54.618. Paillard immediately raised this figure to 59.954 but he almost got killed in the attempt. To beat Paillard, Meiffret selected a special circuit in Germany, the Grenzlandring. Cheered by thousands, he covered 65.115 miles in an hour and could have done more if his motor had been running right. All this required incessant training and complete concentration. Meiffret's philosophy was "to become what you are."

Although his exploit at Grenzlandring brought him great acclaim, it did not bring him any money. In fact, none of Meiffret's rides brought him any money. All his life, he had to fight poverty. He supported himself with odd jobs and with occasional writing. His latest book Mes rendezvous avec la mort, earned him the 1965 Grand Prize for Sports Writing and the Prix Sobrier-Arould of the prestigious Académie Française.

In an effort to improve his position in 1951, he decided to race behind cars instead of motorcycles. Cars are bigger and faster. Here, the man to beat was Alfred Letourneur, an expatriate Frenchman who had covered a measured mile behind a car on the Las Angeles freeway at 108.923 in 1941.

Meiffret's first attempt was behind a Talbot. To his consternation, he could not get past 70 miles an hour. Aerodynamic engineers told him to modify his windscreen. After months of toil and heartbreak he tried again. A 20-mile stretch of road south of Toulouse was especially cleared (even the President of the French Republic was detoured on that day). On his first run, the Talbot faltered. On his second run, he lost contact and was almost flattened by the wind. On his third run, he hit a bump and was in free flight for 50 feet, but he held on and finished the kilometer at 109.100 miles per hour. Letourneur had been beaten, but not by much.

Undisputed record man of the hour and of the kilometer on the road, Meiffret next turned to the track at Montlhery. Here, the Belgian Vanderstuyft had ridden 78.159 an hour behind a motorcycle in 1928. But Montlhery in 1928 was new. In 1952 it was old. The pavement was starting to crack, and the turns were atrocious. The track superintendent shook his head. He had seen many try. But Meiffret was determined. On the appointed day, he rode his first lap at 80 miles per hour. Suddenly, coming out of the turn on the seventh lap, his bicycle started bucking. Nobody knew what actually happened. Perhaps the pedals, which had less than an inch of clearance, scraped. At any rate, Meiffret flew through the air, hit the ground, tumbled three hundred feet, slid another twenty, and came to a rest, a quivering mass of flesh. Horrified attendants carried him to an ambulance, and newspapers announced his imminent death. That night surgeons found five separate skull fractures. Unbelievably, Meiffret lived through this ordeal.

Then followed a long period of recuperation during which he fought as much for his mental sanity as for his physical health. In search of peace, he joined the Trappists at Sept-Fons and led the life of a monk. During this time he made continuous improvements on his bicycle, wrote his first book (Breviary of a Cyclist), and corresponded with hundreds of people. Thus he learned of a new freeway at Lahr in Germany where he might gain permission for another attempt on the flying kilometer. In the fall of 1961, when he was already forty-eight, he reached 115.934 miles per hour. This ride convinced him that he could reach 200 kilometers (124 miles) an hour. Thus we find Meiffret in the summer of 1962 on the freeway at Freiburg, riding like a man possessed.

The Mercedes performed flawlessly. People could not believe their eyes. What they saw was the car in full flight with and arched figure immediately behind, legs whirling, jersey fluttering, wheels quivering. "Allez, allez," gasped Meiffret into the mike. In the car, the speedometer crept past 100 mph, then 110 and 120. Anguished, Zimber looked into his rear-view mirror. How could Meiffret keep himself positioned? It was fantastic.

At the flat, the speed had increased to 127. Faster than an express train, faster than a plummeting skier, faster than a free fall in space. Meiffret's legs were spinning at 3.1 revolutions per second, and each second carried him 190 feet! He was no longer a man on a bike. He was the flying Frenchman, the superman of the bicycle, the magician of the pedals, the eagle of the road, the poet of motion. He knew that he must live in the rarefied atmosphere for eighteen seconds. When he passed the second flag, the chronometers registered 17.580 seconds, equivalent to 127.342 miles an hour.

Meiffret had survived his date with death.

Le Mistral, sur le plateau de Bourgogne, force à 140 à la heure, et la france s'enorgueillit de cette performance au point d'en faire l'un de grandes themes de sa propagande touristique : pensez-donc! Un train qui relie Paris à dijon à 128 de moyenne, c'est fabuleux.

Mais José Meiffret, lui, roule à bicyclette à deux cents à l'heure, si on mettait l'homme et le train côte à côte, au bout de dix km, meiffret précéderait la mistral de trois km. cela parait invraisemblable, incompréhensible--et pourtant c'est ainsi : un homme, en appuyant sur les pédales, roule à deux cents! bien sûr, il lui faut un vélo spécial, un engin mécanique lui coupe le vent. Mais le simple fait de rouler sans tomber, de se tenir en équilibre à cette vitesse phénoménale sur deux simples roues, cela tient du prodige--et, en fait, c'est un prodige.

Lorsque Jacques Anquetil couvre une demi-étape du Tour de France à 46 de moyenne, mes confrères de la Presse manquent d'adjectifs suffisamment forts pour souligner de valeur de l'exploit. Or, je le répète, José Meiffret roule environ cinq fois plus vite qu'Anquetil.